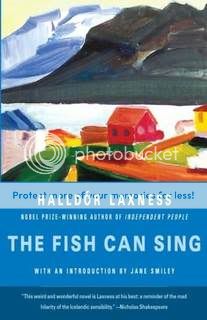

Icelandic title: Brekkukotsannáll (Literally “Annals of Brekkukot”)

Genre: Literary fiction, historical

Year of publication: 1957

Setting & time: Reykjavik area, Iceland; beginning of the 20th century.

This novel by Iceland's only Nobel prize-winner, the first he published after winning the prize, boasts what is the most memorable opening sentence I have ever read in a novel:

"A wise man once said that next to losing its mother, there is nothing more healthy for a child than to lose its father."

Álfgrímur (the narrator of the story) is a young boy abandoned by his mother and raised by his foster-grandparents at Brekkukot, a small house in what is now nearly the center of Reykjavik but was, at the time of the story, one of a small cluster of buildings separate from the commercial and administrative center of town. The house is a haven for people who are down on their luck and acts as a sort of social center for the community and a counterpoint for the bakery which becomes the other centre of Álfgrímur’s life. His plans to become a fisherman begin to change when Garðar Hólm, a world-famous Icelandic singer (who may or may not be anything of the sort), returns to his homeland and awakens Álfgrímur’s interest in singing, but also brings about his inevitable loss of innocence.

I vacillated between reviewing a new (to me) Laxness novel and one I had read before for this challenge, but finally I decided to choose one of my two Laxness favourites, Iceland’s Bell (Íslandsklukkan) or The Fish Can Sing (Brekkukotsannáll). I eventually decided to write about The Fish Can Sing, since it takes place during an era of history that I am interested in. The belle epoque was in full swing in Europe, but while it covers a belle epoque of sorts in the life of the narrator the story of The Fish Can Sing couldn't in other respects be farther away from the grand flowering of culture and science that was taking place across the sea.

The Fish Can Sing is first and foremost a lovely coming of age novel with all the contrasting of experience vs. innocence (and the loss thereof) that this entails, but it is also a mediation on the difference between the pastoral and the cosmopolitan and a somewhat nostalgic snapshot of a less complicated era that is forever gone. On the surface it is a simple story, but there is much going on under that surface. The narrative is more character-driven than plot-based, the prose is simple, beautiful and unpretentious (which can unfortunately not be said of all of Laxness’ novels), and while it hasn’t received the attention that Independent People has, it is thought by some to be Laxness’ true masterpiece. 5 stars.

Below you will find a list of languages it has been translated into,latest edition given in all cases. Some are lamentably translations of translations, but at least the German and Scandinavian editions are translated from the original Icelandic.

Arabic (Hin Tghni Ala'smak; Lebanon, 2010)

Bulgarian (Letopis Na Stopanstvoto Brekukot; 1964)

Czech (Rybí Koncert; 1978)

Danish (År Og Dage I Brattekåd; 1973)

Dutch (Het Visconcert; 2004)

Finnish (Lapsuuden Maisema; 1960

German (Das Fischkonzert; 2002)

Greenlandic (Aallartup Allattugai; 1984)

Hebrew (Gam Ha-Dag Yasir; 1976)

Hungarian (Az Éneklö Hal; 1962)

Italian (Il Concerto Dei Pesci; 2007)

Norwegian (Brekkukotkrønike; 2000)

Polish (Czysty Ton; 1966)

Portugese (Os Peixes Também Sabem Cantar; 2010)

Russian (Brekkukotskaja Letopis, 1954)

Swedish (Tidens Gång I Backstugan; 1967)

Genre: Literary fiction, historical

Year of publication: 1957

Setting & time: Reykjavik area, Iceland; beginning of the 20th century.

This novel by Iceland's only Nobel prize-winner, the first he published after winning the prize, boasts what is the most memorable opening sentence I have ever read in a novel:

"A wise man once said that next to losing its mother, there is nothing more healthy for a child than to lose its father."

Álfgrímur (the narrator of the story) is a young boy abandoned by his mother and raised by his foster-grandparents at Brekkukot, a small house in what is now nearly the center of Reykjavik but was, at the time of the story, one of a small cluster of buildings separate from the commercial and administrative center of town. The house is a haven for people who are down on their luck and acts as a sort of social center for the community and a counterpoint for the bakery which becomes the other centre of Álfgrímur’s life. His plans to become a fisherman begin to change when Garðar Hólm, a world-famous Icelandic singer (who may or may not be anything of the sort), returns to his homeland and awakens Álfgrímur’s interest in singing, but also brings about his inevitable loss of innocence.

I vacillated between reviewing a new (to me) Laxness novel and one I had read before for this challenge, but finally I decided to choose one of my two Laxness favourites, Iceland’s Bell (Íslandsklukkan) or The Fish Can Sing (Brekkukotsannáll). I eventually decided to write about The Fish Can Sing, since it takes place during an era of history that I am interested in. The belle epoque was in full swing in Europe, but while it covers a belle epoque of sorts in the life of the narrator the story of The Fish Can Sing couldn't in other respects be farther away from the grand flowering of culture and science that was taking place across the sea.

The Fish Can Sing is first and foremost a lovely coming of age novel with all the contrasting of experience vs. innocence (and the loss thereof) that this entails, but it is also a mediation on the difference between the pastoral and the cosmopolitan and a somewhat nostalgic snapshot of a less complicated era that is forever gone. On the surface it is a simple story, but there is much going on under that surface. The narrative is more character-driven than plot-based, the prose is simple, beautiful and unpretentious (which can unfortunately not be said of all of Laxness’ novels), and while it hasn’t received the attention that Independent People has, it is thought by some to be Laxness’ true masterpiece. 5 stars.

Below you will find a list of languages it has been translated into,latest edition given in all cases. Some are lamentably translations of translations, but at least the German and Scandinavian editions are translated from the original Icelandic.

Arabic (Hin Tghni Ala'smak; Lebanon, 2010)

Bulgarian (Letopis Na Stopanstvoto Brekukot; 1964)

Czech (Rybí Koncert; 1978)

Danish (År Og Dage I Brattekåd; 1973)

Dutch (Het Visconcert; 2004)

Finnish (Lapsuuden Maisema; 1960

German (Das Fischkonzert; 2002)

Greenlandic (Aallartup Allattugai; 1984)

Hebrew (Gam Ha-Dag Yasir; 1976)

Hungarian (Az Éneklö Hal; 1962)

Italian (Il Concerto Dei Pesci; 2007)

Norwegian (Brekkukotkrønike; 2000)

Polish (Czysty Ton; 1966)

Portugese (Os Peixes Também Sabem Cantar; 2010)

Russian (Brekkukotskaja Letopis, 1954)

Swedish (Tidens Gång I Backstugan; 1967)

Comments